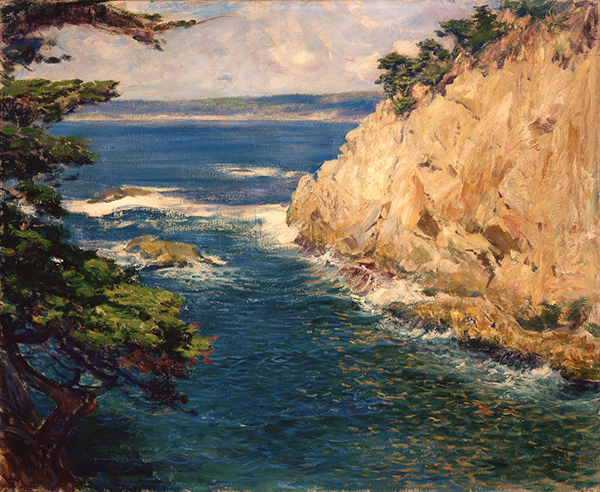

Sublime Wonderlands

Curated by Jean Stern

January 25 – March 14, 2020

Sublime Wonderlands

Focusing on idealized representations of the North American wilderness, Sublime Wonderlands examines long-lasting associations of the American landscape with rugged beauty, limitless resources, and national pride. Assembling a selection of over 40 landscape paintings spanning the late 1800s to the 1980s and ranging in style from American Romanticism to contemporary abstraction, the paintings gathered here chart the development of a persistent narrative about landscape and identity.

Many of the works on view depict regions that would at the turn-of-the-century be designated as National Park areas. Natural monuments such as Yosemite’s Half Dome or Vernal Falls became visual icons and sites of pilgrimage for artists and settlers beginning in the mid-1800s. Indeed, comparable views of the breathtaking mountains, lakes, and waterfalls of Yosemite Valley had been captured by 19th century photographers hired by the United States government to promote tourism and westward expansion through the broad circulation of images depicting these spectacular landmarks. Painters, too, received similar commissions. Importantly, rendering the landscape as untouched by human presence entailed erasing signs of the continent’s Indigenous inhabitants by either removing them from the picture or naturalizing them as features of the landscape.

Yet while emphatically American in content, formal decisions about how to render the landscape developed within a decidedly international context. Many of the painters represented in the exhibition were either born in Europe or spent time studying there, crossing the Atlantic to attend prominent art schools like the Düsseldorf Academy in Germany or the Académie Julian in Paris. By embracing the concept of the sublime—the idea of nature as a powerful, uncontainable force as depicted in European Romantic landscape painting—and by employing stylistic techniques popular with movements like the Barbizon School and French Impressionism, American artists thematically and stylistically associated themselves with their European roots while formulating a uniquely American identity through their iconic content.

We see hints of the Barbizon School’s desire to capture realistic impressions of the landscape in the work of Thomas Hill and William Keith, both of whom were exposed to painters such as Camille Corot and Jean-Francois Millet while studying in France. Unlike the quiet rusticity of the French countryside favored by the Barbizons, however, Hill’s and Keith’s North American wilderness reads as a rugged Arcadia, at once a habitable land of natural wonders and a sublime force to be reckoned with. In German-born Karl Yens’s America the Beautiful, the artist employs the loose brushstrokes and intense colors associated with Impressionism to communicate a tension between allegedly wild nature and American settlement. Yens foregrounds a rocky outcropping and strong surf against an expansive, rough coastline. A stately home overlooks the swelling ocean and an American flag flies conspicuously above the horizon.